Sonoma Water’s History

In 1920, Sonoma County ranked eighth nationally in agricultural production. Water availability had been crucial for the county's agricultural success. Diversions from the Eel River through the Potter Valley Project, initiated in 1906, boosted flows in the Russian River, particularly benefiting northern farming regions.

Between 1935 and 1945, a string of winter floods caused $6.1 million in damage, prompting the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors to seek a flood control plan from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the Russian River Basin.

Following World War II, the Army Corps' 1949 study identified flooding and declining groundwater as major economic threats, and proposed projects like the Coyote Valley Dam and other reservoirs. To execute these plans, the Sonoma County Flood Control and Water Conservation District was established on Oct. 1, 1949. This body would later become the Sonoma County Water Agency and, later still, would be known as Sonoma Water.

1950s

Coyote Valley Dam

In 1950, the U.S. House of Representatives authorized the construction of Coyote Valley Dam near Ukiah. The project began in 1956 and was completed and dedicated in 1959, at a cost of $5.6 million raised through a bond measure. The dam created Lake Mendocino and was operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It helped reduce high winter flows and stored 118,000 acre-feet of water. An acre-foot of water equates to 325,851 gallons. The Sonoma County Water Agency and the Mendocino County Russian River Flood Control and Water Conservation Improvement District share state water rights permits to store water in the reservoir. However, as the local sponsor for the construction of Coyote Valley Dam, the Sonoma County Water Agency has maintained the right to control releases from the water supply pool in Lake Mendocino.

Once water stored in the lake reached the flood control pool, releases were determined by the Army Corps. As the local sponsor for the project, Sonoma Water also assumed responsibility for maintaining channelization works on the Russian River constructed along with Coyote Valley Dam.

Christmas Day floods

Christmas Day floods

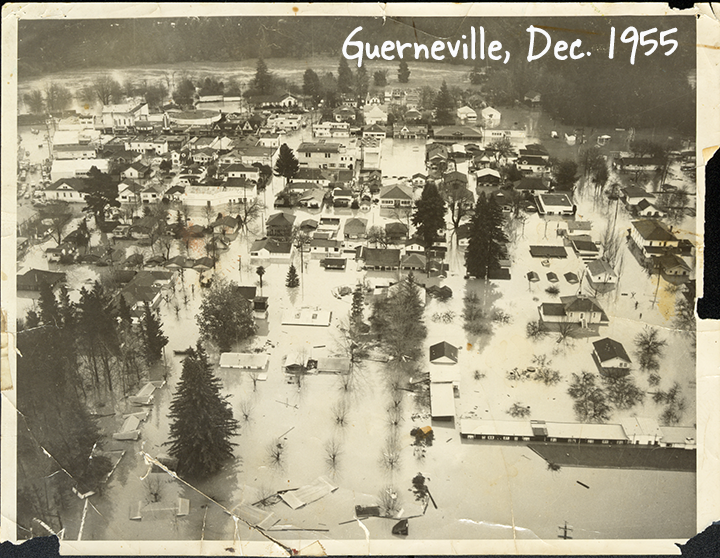

In 1955, Sonoma County suffered from heavy flooding for several days starting on Dec. 25. Flood waters covered 30,000 acres of land and reached a height of 47 feet, underscoring the need for more flood control measures.

Water supply and transmission system

Sonoma Water began providing water to the City of Santa Rosa on May 24, 1959, under a 1956 agreement that set the fees the city was to pay, and the quantities of water Sonoma Water was to provide. To provide sufficient revenues to expand the system, Sonoma Water entered into similar agreements with principal cities and water districts along the route of each ensuing aqueduct before its construction.

The bond measure that funded the Coyote Valley Dam also provided for the initial construction of the Sonoma Water’s water supply and transmission system. The system began simply enough, with a single diversion facility called a Ranney collector at Wohler Bridge, which collected water from a depth of approximately 60 feet in the gravel next to the Russian River and pumped it through the Santa Rosa Aqueduct for 15.6 miles to storage tanks near Lake Ralphine. The Santa Rosa Aqueduct formed the backbone of the Sonoma Water’s delivery system, with all future aqueducts connecting to it.

1960s

Central Sonoma Watershed Project

After repeated catastrophic flooding through the 1950s, four flood detention reservoirs were built in the 1960s on Santa Rosa Creek, Matanzas Creek, Paulin Creek and Brush Creek. Collectively. This integrated network of channels, detention reservoirs and flood facilities are collectively known as the Central Sonoma Watershed Project.

With much of the infrastructure of the Central Sonoma Watershed Project reaching the end of its life expectancy, Sonoma Water and the Natural Resources Conservation Service are currently conducting a vulnerability assessment of the project facilities and plan to publish a new plan for restoration and improvement work to increase community resilience over the next 50 years.

Spring Lake (Santa Rosa Creek Reservoir)

From 1961 to 1964, Sonoma Water constructed Spring Lake as a flood control reservoir and another element of the Central Sonoma Watershed Project. The reservoir, one of Sonoma Water’s most ambitious flood control projects, consists of three earthen dams, two concrete spillways, a diversion structure and conveyance channels. The project diverts floodwaters from Spring Creek and Santa Rosa Creek into Spring Lake, mitigating flood risk to downtown Santa Rosa by temporarily storing flood waters.

In 1958, the project was designed to temporarily store the volume of water generated by a 100-year storm event (in other words, a storm that, based on 1958 records, had a 1 in 100 - or 1 percent - chance of occurring in any year). Only once since the lake's construction, in 1986, has flooding been so severe as to exceed Spring Lake's capacity and activate the emergency spillway. Plans to create a park around the lake didn’t come to fruition until 1973.

Aqueducts

In 1962, two more aqueducts were completed; the Forestville Aqueduct, which provided water to the Forestville Water District, and the 18-mile Petaluma Aqueduct which provided water to the cities of Petaluma, Rohnert Park, Cotati and the Northern Marin Water District. In 1965, the Sonoma Aqueduct was completed along with the Sonoma Booster Station, and the Annadel, Eldridge and Sonoma water storage tanks, supplying water to the City of Sonoma and the Valley of the Moon Water District.

In 1962, two more aqueducts were completed; the Forestville Aqueduct, which provided water to the Forestville Water District, and the 18-mile Petaluma Aqueduct which provided water to the cities of Petaluma, Rohnert Park, Cotati and the Northern Marin Water District. In 1965, the Sonoma Aqueduct was completed along with the Sonoma Booster Station, and the Annadel, Eldridge and Sonoma water storage tanks, supplying water to the City of Sonoma and the Valley of the Moon Water District.

Warm Springs Dam authorized

In 1962, following the second survey report by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Congress authorized a flood control structure and reservoir with recreational facilities on Dry Creek, a major tributary to the Russian River, near Cloverdale. Called Warm Springs Dam, the project was designed to provide 212,000 acre-feet of water supply storage and 130,000 acre-feet of flood control storage in a reservoir to be known as Lake Sonoma. Warm Springs Dam proved to be very controversial. Design and construction were suspended several times by litigation over financing and environmental effects, and ballot initiatives to halt the dam were presented to voters and defeated on three occasions. Lake Sonoma wouldn’t begin storing water until more than four decades after the Army Corps' initial 1937 survey, in 1983.

1970s

The 1970s brought new connections to the Bay Area with the construction of US-101. Demand for water grew along with the growth of the county population as new businesses and families moved to the area, with flows through the Santa Rosa Aqueduct increasing 300% from 1960 to 1970. More collectors were needed as were more aqueducts. The 1974 Agreement for Water Supply gave direction to Sonoma Water to operate, maintain and expand the water supply and transmission system.

This meant a new intertie pipeline from the Russian River to Cotati, additional diversion facilities at the Russian River, an inflatable dam at the diversion site to fill infiltration ponds, booster pumps, storage tanks, emergency wells, a hydroelectric plant at Warm Springs Dam, corrosion control facilities, a water quality early warning system and computerized telemetry systems.

The 1974 Agreement for Water Supply fixed the amount of water to be delivered to the water contractors based on their own estimated needs. The signatories to the agreement were the cities of Santa Rosa, Petaluma, Rohnert Park, Sonoma and Cotati; North Marin Water District; Valley of the Moon Water District and Forestville Water District.

The decade also brought several new federal environmental laws along with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, including the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Air Act, both of 1970 and the Clean Water Act of 1972. Sonoma Water hired its first environmental specialist in 1974 to prepare environmental documentation, studies and reports required by law.

Beginning in 1974, the first of many lawsuits was filed to stop the construction of the dam for alleged violations of the National Environmental Policy Act, and construction was largely blocked until 1980.

1980s

In response to drought conditions in the late 1970s, Sonoma Water launched a water conservation program in 1981 focused on outreach to schools and the landscape industry. Through the program, Sonoma Water distributed free water conservation booklets, bumper stickers, and pencils with the message "use water wisely" to teachers and students at schools in Sonoma and northern Marin counties. Sonoma Water also developed water auditing and leak detection programs and used the Sonoma County Fair to promote conservation.

In 1983, Lake Sonoma began storing water behind the newly completed Warm Springs Dam.

Sonoma Water developed its first Urban Water Management Plan in 1985. The plan, which is updated approximately every five years, most recently in 2020, estimates past, current, and projected water use; describes available conservation measures, including their cost-effectiveness and environmental and other effects; schedules implementation of proposed conservation measures; and estimates the frequency and magnitude of droughts and water supply emergencies. The plan also includes an evaluation of water reclamation possibilities, opportunities for water transfers or exchanges, conservation incentives and public outreach or educational programs.

ln 1986 the operation of Lake Sonoma and Lake Mendocino changed to accommodate the State Water Resources Control Board's Decision 1610, which established minimum in-stream flows for Dry Creek and the Russian River downstream of Lake Mendocino. These flows were designed to support recreation, fish and wildlife, and other beneficial uses of the Russian River.

1990s

In 1994, Sonoma Water became responsible for breaching activities at the mouth of the Russian River estuary, which included mechanically breaching the sandbar that forms at the river mouth to minimize flood risk for low-lying properties along the estuary.

By 1995, concerns for the health of the Russan River were mounting and the community demanded a closer look at the effects of all the river’s diverse uses. Sonoma Water began to communicate with regulatory agencies and environmental groups envisioning improved coordination and collaboration and, in turn, improved management of the Russian River watershed.

In 1995, Sonoma Water hired a fisheries biologist and established the Fisheries Enhancement Program as part of its Natural Resources Section.

Also in 1995, Sonoma Water assumed responsibility from the County of Sonoma for the management of sanitation districts and zones. Today, these include the Occidental, Russian River, Sonoma Valley and South Park Sanitation districts, and the Airport/Larkfield/Wikiup, Geyserville, Penngrove and Sea Ranch sanitation zones.

In the late 1990s, coho salmon were listed as endangered and Chinook salmon and steelhead trout were listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act.